http://www.theguardian.com/science/2015/mar/13/satellites-space-race-andrew-smith

Back in 1945, when science fiction writer Arthur C Clarke conjured up the idea of an Earth-orbiting broadcast satellite, he neglected to patent it: he couldn’t imagine one being built in his lifetime. He wasn’t the only one caught off guard when the Soviet Union sprung a satellite on the world just 12 years later – sleek, silvery Sputnik 1, begetter of a million fancy light fittings and a slew of teen dances.

Since then, thousands more have been flung at the heavens, of which roughly 1,200 remain active. Over the next decade, however, that number is set to double for the simple reason that no technology is more tied to our connected, accelerated third millennium world than this. Yet satellites remain remote and mysterious, drivers of a second space race very few people see.

In 2012, the photographer Toby Smith set out to shed light on this enigmatic industry. He followed the fortunes of three near-identical satellites built for the European operator SES, from the ultra hi-tech plants where they were assembled and tested, through to their bizarre transportation and subsequent launch from far-flung “space ports” on three different continents. What he found was a shadowy technological ecosystem, operating at an obscure tangent to the everyday world that increasingly relies on its ministry.

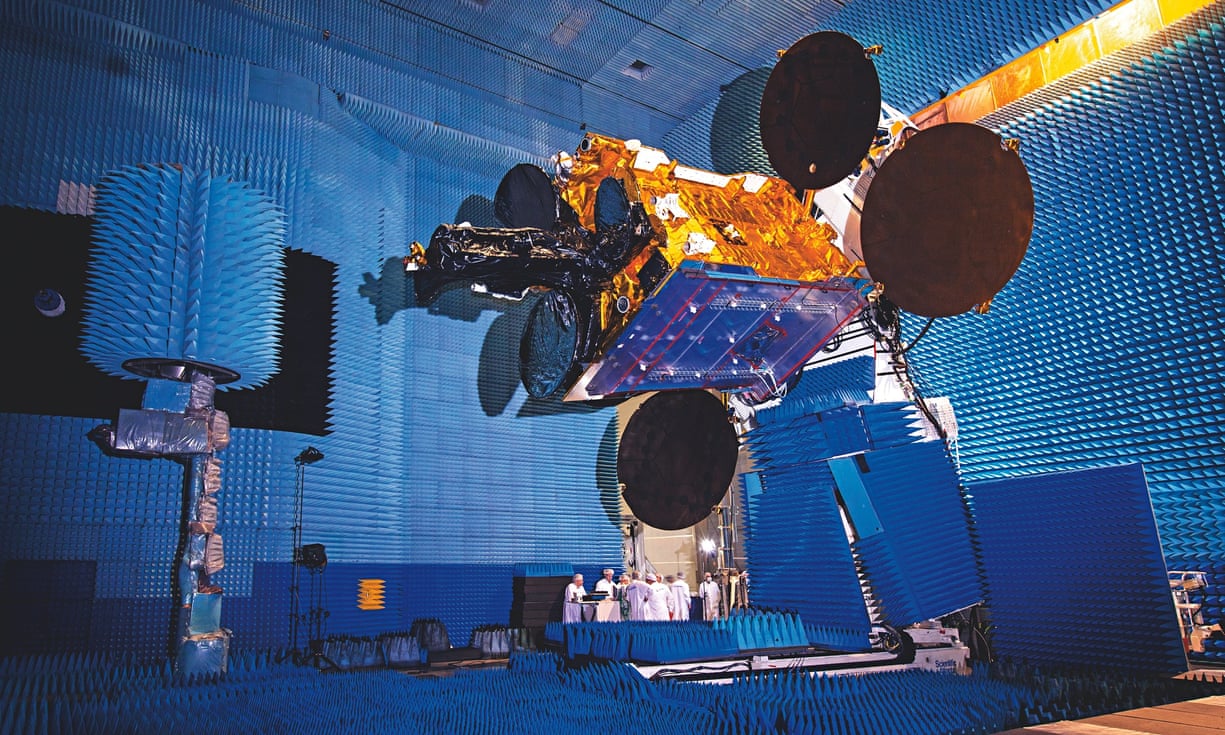

Inside the Airbus Defence and Space facility in ToulouseSmith’s trip began at the vast Airbus Defence and Space facility in Toulouse, where the SES-6 was being prepared for deployment above Latin America, to relay TV signals and other communication data. He quickly found that satellite designers have a different set of imperatives from their Earth-bound peers. “Anything that moves, the engineers hate,” Smith explains. “The whole satellite industry is obsessed with stopping and starting – an abrupt, physical procedure they try to avoid as much as possible.”

What does this mean? As with your car or boiler or laptop, most wear and tear in space comes not from continuous operation but from turning things on and off, so engineers will go to extremes to avoid moving parts. At a cost of between $0.5bn and $1bn, a compromised satellite quickly becomes a financial albatross. In space, no one can whack a sticky valve with a wrench.

Satellite SES-6 is taken to Toulouse airport and loaded on to a cargo planeOnce it had been tested and was ready to go, SES-6 travelled to a launchpad in the former Soviet space port of Baikonur in Kazakhstan. This, the most vulnerable part of the process, is shrouded in secrecy; a watchful team stood guard over the satellite all the way. “It takes four days to transfer it into its 20-tonne, temperature-controlled container,” Smith says. “When it was due to leave Toulouse, I was shipped in for four days, but not told exactly when it would leave the building – it’s a matter of national security when the thing hits the road. So I was waiting around, then suddenly, at 3am one morning, it happened.”

Via a back door at Toulouse airport, SES-6 was loaded on to another Soviet artefact, an Antonov AN-124, the heaviest cargo plane ever made. This was done by a 12-man Ukrainian crew who live in a tobacco-tarnished, bunker-like space inside it and rarely disembark; who fly from secret mission to secret mission, lost in a nomadic netherworld.

At the remote Baikonur cosmodrome in KazakhstanUp to this point, the paths followed by Smith’s three near-identical satellites were broadly similar. But while SES-6 went to Baikonur, to be launched aboard a Proton rocket originally designed for nuclear war, its sister, SES-8, was heading from a Maryland factory to the balmier climes of Florida and the care of PayPal billionaire Elon Musk’s spacefaring upstart, SpaceX. Musk’s ambition to colonise Mars has made headlines, but the first phase of his business plan is based on satellites, where demand is rising and the competition is long in the tooth. His initial problem was a lack of track record, until the offer of a substantial discount on the company’s base launch fee of $60m (already between four and 10 times cheaper than the alternatives) persuaded SES to take a punt.

In space, no one can whack a sticky valve with a wrench

Smith picked up the story of SES-8 as it was being tested at the Maryland HQ of its American manufacturer Orbital Sciences, following it to SpaceX in Cape Canaveral, where the company leases a disused space shuttle pad from Nasa.

SpaceX is like no other aerospace environment. It’s located in a factory once used to assemble jumbo jets near LAX airport. Here, workers in camouflage shorts, Indian skirts and sandals pedal trikes across the shop floor or debate engineering issues over free frozen yoghurt in the canteen, while the CEO sits in full view at a workstation in one corner, wearing a checked shirt and jeans. Unlike the outsource-happy aerospace industry, almost everything to do with its Falcon 9 launch system is manufactured within one gargantuan space, by a local workforce who are encouraged to think unconventionally. If Musk succeeds in his ambition to make the Falcon 9 booster reusable (rocket stages are traditionally lost at sea when spent), he should be able to launch for the cost of fuel alone – about $200,000, by his reckoning. Which would turn the industry upside down and fundamentally change our relationship with space.

The SpaceX Falcon 9 launches satellite SES-8 into space at Cape Canaveral“Going with SpaceX was a bold and risky move for SES,” Smith says. “But the culture there is very open.” Whereas French workers and media tend to be kept in the dark, in case share price-sensitive information leaks out, SpaceX staff often get restricted information from Musk’s Twitter feed.

The 12-man Ukrainian crew fly from secret mission to secret mission, lost in a nomadic netherworld

After several false starts, Musk’s Falcon 9 launched gorgeously into a clear night sky above Florida on 3 December 2013. But nobody celebrated until SES-8 was successfully released into orbit later that day; a failure to do this would have obliged the satellite to use its internal fuel supply for repositioning, attenuating its life. Thirty-three hours later, the mother of all launch parties began.

Smith’s third satellite took another route entirely, aboard the aristocrat of the rocket world, the European Space Agency’s Ariane 5, from a rambling space port in French Guiana, South America. Where the Falcon’s habitat is lean and dynamic, Ariane exists in a bureaucratic haze of forms filed in triplicate, legally enforced 37-and-a-half-hour working weeks and religiously observed lunch breaks, taken with wine. Smith spent four weeks in the French dependency (all prospects of independence have been blown by its proximity to the equator and the consequent advantage in launching rockets). He was forced to guess at progress: if an engineer came to breakfast in the same clothes as the previous day, Smith knew they’d been working through the night, and that that day’s schedule was unlikely to hold.

Engineers at work at the space port in French GuianaYet there was much to admire, he says. “For all the bureaucracy of the French culture, you could see where the TGV had come from, and all those quirky but brilliant cars. When you meet French industrialists and engineers, they really love what they do and have a clear sense of responsibility and teamwork. That’s very different from America’s capitalism. In a weird way, the paperwork and bureaucracy seems to empower and bind them.”

Which may be why Ariane has established itself as the gold standard of rocketry, with a full order book and an unprecedented run of almost 60 successful launches over 20 years. All the same, as technology advances and satellites grow smaller, most experts agree that Ariane, with its 20-tonne payload (a third more than the Falcon 9), is too big and expensive to remain competitive for ever. The European Space Agency has now committed €4bn to producing Ariane 6, a more compact and efficient vehicle aimed directly at SpaceX.

Asked what surprised him most about his trip through the satellite beau monde, Smith doesn’t hesitate. “The amount of international cooperation and diversity,” he says. “Engineers I met from Portsmouth, making fuel tanks for Airbus in Toulouse, turned up in French Guiana, where I met their end-clients from Georgia. The Proton rocket, which was designed to strike the eastern seaboard of the US, is now jointly US-Russia owned. I heard so many international accents wherever I went. There’s something amazing about that, this pinnacle of engineering involving a huge international effort, aimed at launching a satellite like SES-6, to sit above Brazil and help broadcast the World Cup. All this effort for such a simple goal: communication. I loved that.”

Comments