"Morgellons (também conhecido como doença ou síndrome de Morgellons), é um nome dado por Mary Leitão, após uma condição proposta pela Centers for Disease Control and Prevention como dermopatia inexplicável, caracterizada por uma variedade de sintomas na pele, como formigamento, mordeduras e sensações de ferrões." Morgellons (also known as Morgellons disease) is a name given by Mary Leitão after a condition proposed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as an unexplained dermopathy characterized by a variety of skin symptoms such as tingling, biting and sensations of stings. Sintomas e diagnósticos Morgellons não é reconhecido como uma doença única e tem atualmente nenhuma lista de sintomas ou diagnóstico diferencial que é geralmente aceito pela comunidade médica. Os pacientes geralmente fazem o auto-diagnostico com base em relatos da mídia e informação a partir da Internet. O principal sintoma da suposta Morgellons é "uma crença fixa" que as fibras são incorporadas em ou de extrusão a partir da pele. Rhonda Casey, chefe de pediatria da Universidade Estadual de Oklahoma Medical Center, enquanto trabalhava com o Centro Estadual de Oklahoma Universidade de Ciências da Saúde (OSU-CHS) para a investigação da doença de Morgellons, afirmou que seus pacientes pareciam doentes com sintomas neurológicos, que incluiu confusão, dificuldade para andar e controlar o seu pé (queda do pé), e uma boca flacidez quando se fala. Symptoms and Diagnoses Morgellons is not recognized as a single disease and currently has no list of symptoms or differential diagnosis that is generally accepted by the medical community. Patients usually do self-diagnosis based on media reports and information from the Internet. The main symptom of the supposed Morgellons is "a fixed belief" that the fibers are incorporated into or extruded from the skin. Rhonda Casey, chief of pediatrics at the Oklahoma State University Medical Center while working with the Oklahoma State University University of Health Sciences (OSU-CHS) to investigate Morgellons disease, said her patients appeared to be ill with neurological symptoms, which included confusion, difficulty walking and controlling your foot (falling of the foot), and a sagging mouth when speaking. https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Morgellons LEIA MATÉRIAS PERTINENTES AO ASSUNTO NO LINK: https://nenedesorocaba.blogspot.com/2...

MORGILLONS - PESQUISA: NALY DE ARAÚJO LEITE

MORGELLONS// DOENÇA TERRORISTA // HOLOCAUSTO DO SÉCULO// COMUNIDADE MÉDICA E MAUS TRATOS.

Dentre materiais químicos e contaminantes na lama de Brumadinho temos composição encontrada nos Morgellons.

Among chemical materials and contaminants in Brumadinho mud we have a composition found in Morgellons.

Há verba para experimentação humana com base militarista e no subterfúgio de defesa territorial, mas não há verba para aplicar na Previdência Social.

"Subvida, Subhumanismo", Subdesenvolvidos e Ratos de Laboratório.

Countries are not able to pay Social Security fair and full, as it would be fair, but they create Viral and Bacterial Projects that can lead the population the need of such Welfare.

There is money for human experimentation with a militarist base and in the subterfuge of territorial defense, but there is no money to apply in Social Security.

"Subdued, Subhumanism," Underdeveloped and Laboratory Mice.

https://www2.camara.leg.br/atividade-legislativa/comissoes/comissoes-permanentes/cdhm/comite-brasileiro-de-direitos-humanos-e-politica-externa/ProgAcMundPessDef.html

1- Worldwide publications on MORGELLONS, can check through You Tube and medical channels.

2 - Next came ZICA AND CHICUGUNHA;

3 - The creation of the ZIKA virus in laboratories;

4 - WHO reports that there were no reports of contamination by the Zika virus during Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro.

One fact is obvious, mosquitoes did not "gather" to implement the economy and tourism during the Olympics, unless "this gathering follows a laboratory and human control line."

Do not doubt that viruses and bacteria can be created and modified in laboratories, biological warfare has these weapons as weapons.

Experimental targets are second- and third-world countries, and when in first-world countries for not being very evident, they use people of color, race against whom prejudice prevails, and the poorer districts of the big cities of these countries .

by Kate Knibbs

published April 8, 2015 @ 07:49

Mitchell talked about Morgellons syndrome, a disease whose victims claim that their skins are filled with parasitic fibers, often arising from wounds and injuries. In addition, the disease would cause fatigue and other health problems associated with itchy skin. Morgellons disease is not accepted as a reality within the medical community. Many physicians and researchers credit the internet for the creation of symptoms to spread Morgellons self-diagnoses as a kind of folie à la deux digital. "It seems to be a socially transmitted disease on the internet," said Robert E. Bartholomew, the mass illusionist (yes, there is).

In 2008, a panel of doctors answered questions about Morgellons for the Washington Post. At the time, Dr. Jeffrey Meffert explicitly accused the Internet and digital communities as guilty of the spread of the disease. Skeptics do not see Morgellons syndrome as a virus, but rather as a lie that viralized.

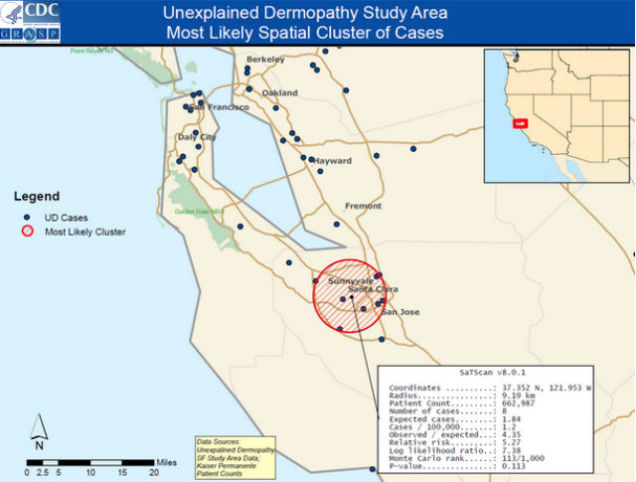

In 2012, the US Government's Centers for Disease Control (CDC) investigated Morgellons and concluded that it is a psychosomatic illness. A CDC spokeswoman told me that the center did not collect any more reports on the syndrome since the study was published. Many physicians believe that people who self-diagnose with Morgellons have illusions of parasitosis and infestation, and inflict the bruises on themselves. In other words, it's all their head.

People who identify themselves as Morgellons patients - or "Morgies" - are annoyed by this assessment. And where do people go when they think the medical community will reject them? For the internet! People who have what the CDC calls "unexplained dermopathy" are largely self-diagnosed through web searches, or diagnosed by other community members over the internet. The term "Morgellons" spread through the web because of a Pennsylvania state woman named Mary Leitao, who blogged about her son's unexplained skin disease in 2002 and called it "Morgellons," referring to a obscure disease described in the 17th century.

Most Morgellons patients began reporting the symptoms after 2002, which causes some more skeptical physicians to believe that information about Morgellons on the Internet infects people with a mass illusion by offering too vague information for them to understand which is making them feel bad.

Feeling betrayed by modern medicine, people began to develop a collective unofficial digital bibliography about the disease. They organized themselves into groups such as the Morgellons Research Network, in addition to the closed Morgellons Research Foundation, and the Charles E. Holman Morgellons Disease Foundation. Joni Mitchell has even talked about abandoning music to focus his energies on publicizing the syndrome. When you take a look at Morgellons' victim support groups on the internet, you may notice a clear emphasis on proving that Morgies are not simply crazy: they are people obsessed with documenting such fibers in photographs and videos.

The persistence and outcry of the digital community has prompted the CDC to create a million-dollar task force to investigate the disease. The fact that the CDC concluded that the problem is probably psychological did not cause the Morgies to stop seeking a cure.

Illusion or not, the paranoia explains

Some of the efforts to prove that Morgellons syndrome is real certainly do much to remind what conspiracy theorists do on the internet. It does not help much the fact that groups believe the disease is caused by chemical compounds released by airplanes - the chemical trails, or "chemtrails."

More than 14,000 people enrolled in the Morgellons Research Foundation, most of them women. It is true that there is a lot of paranoid conspiracy among the Morgies, but many of them simply want to understand why doctors can not explain the itch with a better explanation than "it is the symptom of a psychological illness."

So, is it a lie or not?

One thing needs to be said-and it's usually said by people with Morgellons and some doctors, like Dr. Greg Smith: The diagnosis of the illusion is wrong. Dr. Anne Louise Oaklander, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School who studies neurology and itching, explained to the Guardian that this is a case of a group of misdiagnosed people:

"In my experience, patients with Morgellons are doing their best to believe that the symptoms are real. They suffer from a chronic disease of itching that has not been diagnosed. They were mistreated by the medical community. "

Looking at the conspiratorial tendencies of some patients with Morgellons and the lack of medical evidence pointing to any physical issue, it is tempting to simply label the disease as some web-like malice perpetuated. But that would be a crude stance. We do not know if this disease - or set of diseases - called Morgellons by many people is a psychological or neurological issue. Maybe it's caused by some parasitic as yet undiscovered.

Even if the medical community never finds a physical root for the causes of Morgellons, the pain suffered by those who identify with it is clearly real. Joni Mitchell is not kidding. And whether or not the internet contributed to the popularity of Morgellons syndrome, it just did it to function as a support system for a desperate community to be heard.

Photo: Collage of lesions Morgellons via David / Flickr

https://gizmodo.uol.com.br/por-dentro-da-sindrome-de-morgellons-a-doenca-da-internet/

The medical records revealed that M.C. had been to the emergency department on three previous occasions:

Four months earlier, he had been admitted for a suicide attempt by heroin overdose. He cited drug use as his stressor and claimed command auditory hallucinations telling him to “end it all.”

A month later, he returned with similar complaints, describing his stressor as being asked to leave the Salvation Army because of drug use and curfew violation.

One week before his presentation, M.C. returned complaining of “bugs crawling out of my skin” for 1 week; the bugs originated from scabs acquired while working as an aluminum press operator. He admitted to a history of crack, cocaine, and heroin use terminating 1 month prior. He received a 10-day course of mupirocin cream and diphenhydramine and a referral to a psychiatry clinic.

At all three visits, the patient’s urine drug screen was positive for cocaine and opiates.

Current Findings

The physical findings included a heart rate of 117 bpm and a blood pressure of 144/90 mm Hg. The patient was noted to be mildly distressed and anxious; he was oriented to person, place, and time and displayed multiple scabs, which he was picking. No bugs or parasites were visible. Additionally, a urine drug screen was positive for cocaine and opiates ( Appendix 1 ). The patient received lorazepam, 1 mg, in the emergency

During his psychiatric interview, M.C. reiterated, “I fell asleep in an abandoned building last week and woke up and found I was infested with bugs.” He complained of “seeing and feeling” bugs on his skin, that his vision was distorted by “bugs in my eyes,” and that “my urine smells funny.” He experienced an urgency to pick the “worms” from his hair follicles, which yielded a sense of relief. He reported no auditory or visual

Day Two

The following morning, M.C. reported no itching, noting it only occurred at night. Later he recounted “white mites and worms” emerging from his “sores” upon squeezing and agreed to collect a specimen for examination. Clonidine was added for presumptive opiate withdrawal. The patient also requested a nutrition consultation, claiming to have lost 40 lb in 2.5 months (body mass index=22.1 kg/m 2 ). A dermatologist

M.C. continued to complain of bugs in his skin and frustration that the dermatologist did not provide him with a medication to kill the insects. He continued to endorse suicidal ideation. The patient consented to treatment with cephalexin, 250 mg four times a day for 2 weeks, and olanzapine when it was specifically explained to him that they would help treat the feeling that bugs were infesting his skin.

Day Four

The patient was noted in the early morning to be lying in his neatly arranged bed complaining of itching and seeing bugs and worms—“their legs coming from bites”—on his arms, neck, torso, and legs. Despite persisting symptoms, M.C. insisted on discharge on the evening of day four because of occupational obligations; he reported no suicidal ideation and contracted for safety, agreeing only to continue cephalexin.

M.C. returned twice to the emergency department:

Six days postdischarge, he returned complaining of skin irritation and itching. He stated he had been diagnosed with scabies and had received permethrin cream from an unknown physician 3 days earlier. He reported no suicidal ideation but admitted to using heroin and cocaine that day. Upon examination M.C. was calm, cooperative, and well oriented. Multiple ulcers were appreciated on his scalp and extremities with blood at the bases. No burrows or other signs of scabies were appreciated. The patient was referred to outpatient dermatology.

Two months after discharge, M.C. was seen for a complaint of “scabies all over me” and considerable itching despite the use of permethrin. He had suicidal ideation and had just been discharged from a local crisis center. He admitted to using heroin earlier in the day. The patient was well oriented and picking at sores. A urine drug screen was positive for benzodiazepines, cocaine, amphetamines, tetrahydrocannabinol, opiates, and barbiturates. He was discharged with permethrin and diphenhydramine.

The patient was ultimately lost to follow-up and as of the writing of this article was incarcerated for possession of crack cocaine.

Diagnosing M.C.’s Chief Complaint

Since appearing in the literature at the turn of the 19th century, delusions of parasitosis—the conviction of infestation with parasites in the absence of objective evidence—has presented dilemmas in diagnosis and management. It has variously been classified a as a phobic disorder, delusional disorder, tactile hallucinosis, and monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis (2) . Today the classification schema of the symptom complex of delusions of parasitosis consists of three categories: 1) primary psychotic, 2) secondary functional (underlying psychiatric disorder), 3) secondary organic ( Appendix 2 ). The primary form (the most common) (2) is marked by the absence of other disturbances of thought or thought process and is classified under delusional disorder, somatic type, in DSM-IV-TR (3) . Notably, delusions of parasitosis occupy the nexus of delusion and hallucination because most patients experience tactile and/or visual and auditory hallucinations of parasites as well as a fixed belief of infestation (4) . The DSM-IV specifies that a diagnosis of delusional disorder still applies in this context: “tactile and olfactory hallucinations may be present in Delusional Disorder if they are related to the delusional theme” (5) .

Epidemiology

Delusions of parasitosis occur most often in patients over 50, with an equal sex ratio for patients younger than 50 and a 2:1 female predominance in those over 50; men commonly present at an earlier age. Bimodal peaks occur at 20–30 years and greater than 50. The prevalence is higher in patients with less education and of lower socioeconomic status. Around 10% of cases present as folie á deux (shared psychotic disorder). Because the American literature on delusions of parasitosis consists mainly of case reports and series, the incidence of the disorder is unknown but considered extremely low. For example, the incidence of delusions of parasitosis in southwest Germany was estimated at 83.2 per million per year. The incidence of past psychiatric disorders is actually low in delusions of parasitosis patients, and a small percentage of patients have a history of dermatologic conditions (6 , 7) .

Phenomenology

The patients’ confidence in their delusional system often manifests in the “matchbox sign”—patients bring in particles of lint, skin, paper, or food for inspection by health professionals—and the fact that 90% of the patients present for nonpsychiatric care, generally refusing subsequent psychiatric evaluation. Many patients describe detailed lifecycles for their parasites and are able to draw the organisms, even in the absence of visual hallucinations. Reports describe patients developing elaborate cleansing rituals and self-mutilation to remove the parasites (6) . Before modern psychopharmacology, the remission rate for delusions of parasitosis was 33.9%; more recent data cites a rate of 51.9%, with relapse remaining common (7) .

Addressing the differential diagnosis

The first step in approaching a patient with apparent delusions of parasitosis is to assess for objective evidence of infection (especially scabies) or other skin conditions such as Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis). Next, the strength of the patient’s conviction should be assessed to distinguish delusions of parasitosis from hypochondriasis or obsessive-compulsive disorder, in which patients generally maintain relative insight regarding their conditions. Once the patient is deemed truly delusional, an attempt should be made to discern between primary and secondary delusions of parasitosis and to assess the degree of functional impairment. Patient rapport is critical to successful treatment and compliance.

It is important then to investigate potential medical conditions that may underlie the delusions. Specifically, conditions marked by symptoms of itching or abnormal skin perception (8) , including liver failure, obstructive jaundice, renal failure, anemia, vitamin deficiencies, and HIV/AIDS, are vital to consider because they represent potentially treatable underlying etiologies. In M.C.’s case, though, clinical and laboratory evaluation uncovered cocaine use as the only suspicious secondary organic cause.

Formication, a tactile hallucination of something creeping or crawling on or under the skin, is often referenced and is reported by 13%–32% of cocaine abusers (“cocaine bugs”). Formication is hypothesized to result from parietal lobe stimulation (8) . It is important, though, to recognize that delusions of parasitosis in younger patients are more likely to have an underlying cause and not to dismiss prematurely M.C.’s symptoms as substance-induced psychosis. Most cocaine users are familiar with formication, maintain cognizance of it as a hallucination, and do not go on to form delusions (9) . Although reports suggest that most cocaine psychoses abate within 24–48 hours of discontinuation (10 , 11) , M.C. came to the emergency department with a systematized delusion about his infestation, including an attributional narrative (sleeping in an abandoned house, preexisting work-related lesions), that was stable over at least 1 week. However, reports, although uncommon, exist of chronic psychoses in long-standing, heavy users (12 , 13) . Given his suicidal ideation and history of attempt, it was critical to approach his chief complaint with caution and seriousness because it may have signaled a psychiatric emergency; it is not uncommon for patients with delusions of parasitosis to experience depression and suicidal ideation with the motivation to end infestation, and there is at least one report of fatal delusions of parasitosis in which a 40-year-old man completed suicide during treatment (14) . Finally, because M.C. agreed to admission to the voluntary psychiatric service for the stated purpose of using social work services, malingering must be considered.

M.C. was diagnosed with cocaine- and/or schizophrenia-related delusions of parasitosis, although a primary delusional disorder, exacerbated by cocaine use, remained under consideration.

How This Case Fits Into the Literature

In M.C.’s case, as in many delusions of parasitosis cases, confident categorization of his symptoms is challenging given his inconsistently self-reported psychiatric history (none, schizophrenia, and depression) and positive drug screens. In particular, case reports have linked cocaine psychosis with delusions of parasitosis (distinct from classic formication) (15) ; delusions of parasitosis have also been reported in the context of schizophrenia (3 , 16) . Taken together, suspicion is high for a secondary organic and/or functional etiology. The potential interaction between multiple secondary factors in delusions of parasitosis is unknown. A secondary etiology would help explain M.C.’s younger age (the mean is the sixth decade of life), earlier presentation in disease course (the mean is 1 year), and unusual claim of ocular involvement (7 , 17) . Although inadequate follow-up complicates interpretation, M.C.’s apparent co-occurring somatic delusions of weight loss and urine odor represent interesting phenomena; one other report exists of delusions of parasitosis with the delusion of body odor in a schizophrenic patient (16) . Phenomenologically, though, M.C.’s insistence of a dermatologic condition with detailed delusions, his skepticism of psychiatric involvement, and the persistence of the condition comport with current reports.

A controversial phenomenon possibly related to delusions of parasitosis inspiring discussion and media attention is Morgellons’s disease. As in delusions of parasitosis, patients describe insects/parasites crawling on or under the skin, are convinced they are infested and contagious, and produce physical “evidence” of infestation. In particular, though, patients complain of fibers extruding from the skin; such particles produced for examination have been variously identified as cellulose, fibers with “autofluorescence,” fuzz balls, specks, granules, Strongyloides stercoralis, Cryptococcus neoformans , “alternative cellular energy pigments,” and various bacteria. In no case, however, has an infectious etiology for these mysterious symptoms been confirmed. Morgellons’s disease is largely regarded in the dermatology literature as a manifestation of delusions of parasitosis (and potentially a means of promoting patient rapport through destigmatization), despite the efforts of the Morgellons Research Foundation to promulgate an infectious rather than a neuropsychiatric etiology. Until a treatable infectious component is identified, patients can continue to be treated with neuroleptics—pimozide, risperidone, aripiprazole—which have been reportedly effective (18 , 19) .

Current Etiologic Hypotheses

The debate over the classification and etiology of delusions of parasitosis has revolved around a central question: do delusions of parasitosis reflect a delusional system that arises in response to anomalous sensory perceptions (sensorial view), or does a primary delusion “induce” supporting hallucinations (cognitive view) (4 , 8) ? Etiologic hypotheses have arisen addressing this paradox, and it now appears likely that both mechanisms contribute in different patients, suggesting that delusions of parasitosis are not a homogenous entity. For years, the dopamine D 2 receptor has been implicated in the genesis of psychotic symptoms, including the characteristic of delusions of parasitosis. Involvement of the D 2 receptor in the mesolimbic system could account for the successful use of typical and atypical antipsychotics in treating the primary delusional disorder (6) . This has been traditionally viewed as support for the cognitive view of delusions of parasitosis. However, it is now believed that pimozide, a highly potent typical antipsychotic and the classic treatment for delusions of parasitosis, antagonizes central opiate in addition to D 2 receptors, which may mitigate pruritus and formication that underlie/accompany the delusion of infestation (6 , 20) . In fact, pimozide has effectively treated formication in the absence of delusion (e.g., in delirium tremens). Furthermore, naloxone, an opioid receptor antagonist (21) , has been used to treat cases of delusions of parasitosis, supporting the sensorial view.

A recently proposed hypothesis focuses on the decreased function of the striatal dopamine transporter. This presynaptic protein is responsible for dopamine reuptake and hence modulates the concentration of synaptic dopamine and the duration of synaptic signals. It follows that decreased functioning of the transporter results in dysregulation of extracellular dopamine concentration. The authors propose that both primary and secondary delusions of parasitosis develop because of dysfunctional striatal dopamine transporter (3) . Primary forms result from an exaggeration of age-related striatal dopamine transporter density decrease (there is a mean physiologic decrease in striatal dopamine transporter density of 6%–8% per decade), which would help explain the prevalence of cases in patients over 50 (3 , 6) . Secondary etiologies of delusions of parasitosis affect the striatal dopamine transporter through a variety of mechanisms ( Table 1 ). Psychostimulants, for example, are known to inhibit the striatal dopamine transporter, resulting in increased dopamine levels. Psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and depression are thought to decrease striatal dopamine transporter binding (3) .

Enlarge table

Other studies offer a connection between delusions of parasitosis and cerebral hypoperfusion documented by single photon emission computed tomography. It has been found that active delusional thought is associated with hypoperfusion of the left temporal and parietal lobes. Blood flow normalizes with the resolution of the delusion (22) . Some argue that successful t

The majority of case reports and reviews of delusions of parasitosis have concentrated on defining a demographic profile, investigating associated conditions, describing response to treatment, and suggesting neurophysiologic etiologies. Given the growing evidence and interest for cognitive and affective models of delusion formation, maintenance, and content (24) , an integrated, neuropsychiatric narrative of M.C.’s delusions of parasitosis is fruitful and contextualizes the particular presentation and course of illness.

First, it is reasonable to regard M.C. as a psychosis-prone individual. Although it remains undocumented, his stated history of schizophrenia is supported by complaints of command auditory hallucinations and prior treatment with antipsychotics. It is not possible to determine with confidence the etiology of M.C.’s past psychiatric history due to presumed long-term drug use. Indeed, it is well-documented that cocaine increases the risk for psychotic experiences (one of Freud’s patients treated with cocaine developed delusions of parasitosis) (25) . The most common form of cocaine-induced psychosis is paranoid delusions. Studies have identified risk factors for true psychosis formation in cocaine users as male sex, lower body mass index, earlier initiation of regular use, and greater degree of use (12) .

It seems intuitive that M.C.’s psychosis proneness and substance use contributed in concert to the development of his delusions of parasitosis. It has been found that in schizophrenic patients, chronic substance abuse correlates with significantly increased rates of visual and olfactory hallucinations ( Table 2 ). Furthermore, substance abuse is associated with decreased medication responsiveness in schizophrenic and bipolar patients with auditory and tactile hallucinations (26) . Perhaps this is related to the previously discussed findings that schizophrenia and cocaine act at the striatal dopamine transporter in distinct ways to increase dopamine levels (3) . In addition, it has been posited that auditory and tactile hallucinations are associated with changes in the superior and inferior temporal lobes in schizophrenia patients; drug use may contribute to the development of psychosis in these compromised individuals by accelerating brain tissue loss (26) .